(As published on July 25, 2014 in the Huffington Post http://www.huffingtonpost.com/stephen-finger/national-als-registry_b_5620631.html)

Yesterday the first paper related to the National ALS Registry (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6307a1.htm?s_cid=ss6307a1_e or http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6307.pdf ) was released. The ALS Registry is a very difficult project. Because ALS is not a nationally notifiable condition, it is difficult to accurately identify every patient. This study aims to get an idea of the population of ALS patients by collecting data through to two different means. Both datasets are worthwhile. However, both are also imperfect. My concerns are not related to the long-term value of the Registry. My concern is that this study’s conclusions are based on the idea that the combination of the two imperfect studies captures the entire population. There is absolutely nothing in the data that suggests this is the case. Any results based on this assumption are at best flawed, and at worst disingenuous and reckless. It is counterproductive to disseminate statistics that we know are wrong. The results are already being quoted by ALS organizations and the media. I cannot understand how the CDC or the ALS organizations can justify pretending that these results are representative of the US ALS population.

The database portion of the project began in 2006. It includes administrative data from four major sources. These sources combined cover 90 million patients. There are well over 300 million people in the US. Therefore, we know these databases will not cover every patient.

The registry was launched in 2010 and requires patients to self-enroll on the website. Again, this is imperfect system for trying to capture data from every ALS patient. Not everyone has access to the web or is willing to fill out these forms, especially after being given a diagnosis of this magnitude.

Both of these approaches are useful and should contribute to our knowledge of US patients. However, it is unrealistic to think that combined they have captured every single patient. Therefore, using them to calculate prevalence in an unadjusted manner is incorrect. In addition, neither source is a random sample, so any demographic findings are as likely to be the result of the selection methodology as they are to be of the result of the true underlying characteristics of the entire ALS population.

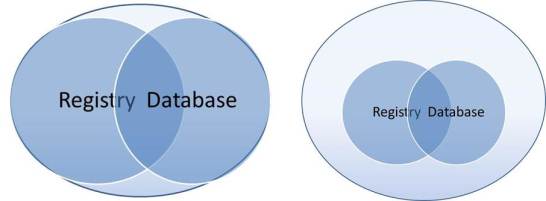

For example, there are 10,261 cases identified in the databases. The registry identifies 3,715 patients. If we believe either one of these databases was doing a good job capturing all of the patients, we would expect there to be substantial overlap. This is not the case. Less than one half of the registry patients also appear in the database. This suggests not only shortfalls in the databases to capture all patients, but it also suggests that if we had other means of identifying patients, we would likely be able to find many more patients who have not appeared in either source. The article shows us that we have been able to identify 12,187 cases using the registry and four government databases. It does not identify how many patients are likely to be living in the US at a given time. The prevalence calculation is at best a back of the envelope estimate. It should have been presented as such.

US ALS Population as Presented. True US ALS Population?

The databases also cover a much older sample. They include Medicare, Veterans Benefits Administration and Social Security Administration data. Each of these sources is highly skewed to an older population. Using this data to calculate the age distribution of ALS patients in the country is absurd. Less than one-third of registry respondents under the age of 50 are in the database. Restricting the data to patients under 40, only one-fourth of the registry patients appear in the database. The registry says almost 10% of patients are under 40. The database says only 3%. One or both of these sources is obviously biased. Simply averaging two incorrect figures isn’t necessarily going to give us something better. The database obviously does a bad job identifying younger patients, so unless the registry is capturing all of those missed patients, the demographic data is going to be wildly incorrect. Again, why are we presenting this data?

The paper also reports some education and employment statistics from the registry. Without considering who is likely to appear in the registry, these numbers must be taken with a grain of salt. I do not think anyone believes that college graduates are 50% more likely to get ALS. To the authors’ credit they note the limitations of these sections though they are still being picked up in the press.

I still have hope that the registry will be a valuable tool for researchers. I have personally taken some of the surveys through the registry and believe they ask intelligent questions. The registry has the potential to help identify things like environmental risks. However without knowing more about who is in the registry, it is grossly premature to try to use this information to calculate representative figures for the entire US population. I am highly discouraged that this initial paper tries to make those claims. There is a shortage of good data related to ALS, so any data that is published becomes “commonly accepted”. Therefore, we have the utmost responsibility to make sure we are not providing misinformation.

I respectfully ask the article’s authors, as well as the organizations publicizing these results, to clarify the shortcomings of their conclusions before these results become taken as fact.